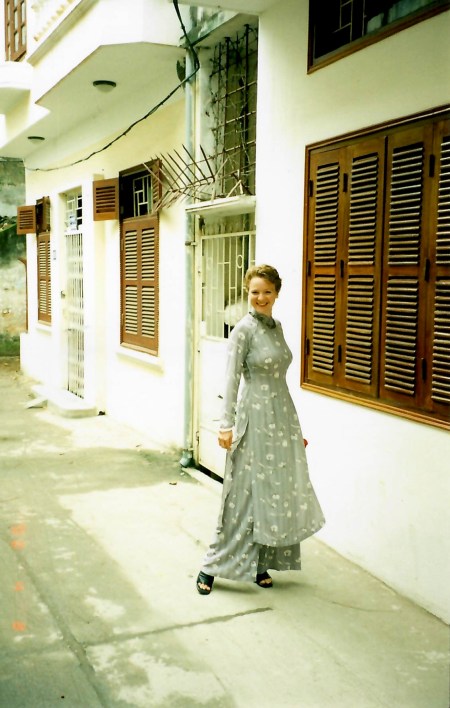

Who knew that decades later we’d call this “cultural appropriation?” Having an áo dài made was a right of passage for every female expatriate in Vietnam.

In the year 2000, I was a newlywed expatriate living in Hà Nội, Vietnam. My promising young husband Ken was a Fulbright scholar, conducting field research for his PhD dissertation. It was best for his research and for our ability to learn Vietnamese, he thought, if we lived in the Bách Khoa neighborhood, with its polytechnic students and middle-class families, and I thought it all sounded like an adventure. Vietnam had just opened up its economy— Đổi Mới was the Vietnamese perestroika—and foreigners and their hard currency were both very welcome.

We rented a “modern” townhouse, sandwiched between identical properties owned by the landlady’s family on one side, and her brother and his family on the other. The houses were made entirely of concrete, floored with slick ceramic tile and lit with icy fluorescents. It offered no climate control beyond ceiling fans.

Above the ground-floor kitchen and common living area, the second and third floors were effectively single large bedrooms and baths stacked vertically, with doors connecting the neighboring houses through the bedrooms. As foreign tenants, we were permitted to bolt those doors from inside, although our landlady, Older Sister Lan, regularly entered the ground floor ostensibly to chat, but really to look into the fridge and see what her foreigners were eating.

It was an absurd amount of room for two people living temporarily abroad, and it was our first house. Our American dollars went far. Our wooden furniture was built to order and delivered by pedicab. We visited the traditional ceramics village of Bát Tràng and bought more dishes than we’d ever use. I would buy buckets of roses from the market around the corner for a few dollars, and fill enormous Chinese-manufactured vases with them in every room. We were young enough that the lack of heat in the winter and the inadequate ceiling fans in the summer were authentic. I loved the mosquito nets. For a young woman from the Midwestern American suburbs, they were the epitome of tropical Asian romance, and I relished lying in bed listening to the frustration of the mosquitoes whining on the other side.

On a steamy June evening, we had retired only under the net and a single sheet. Ken was already asleep, but I was tossing a bit in the heat. Something twitched through my hair. Half-asleep, I ignored it—it was surely just some bug, and I was not a delicate flower so easily frightened–until I felt it again. I sat up in the dark. A tiny quick shadow zipped underneath my pillow. Another oval shadow rested on the mosquito net. Before I emerged from underneath the net, I awoke Ken—“there’s something in the bed”—and then I turned on the light.

Dozens of enormous brown tropical cockroaches were scattered across the pearlescent ceramic floor and were gripping the walls. Cockroaches were clinging to the mosquito net, with the most determined ones making their way underneath it. Reflexively, we grabbed our plastic indoor sandals and began whacking them all into oblivion.

These were hardly the first such cockroaches we’d seen in Vietnam, but they were legion, and acting bizarrely. Some launched themselves into flight, but fell to the floor, like bombers running out of gas. Other would climb part-way up the walls or mosquito net, only to slip back down. Instead of darting away into the crevices to escape the light, they crawled in aimless circles on the floor.

We hit them on the walls, we scraped them off the mosquito net, and we smacked them flat on the floors, yelping at each other in horror. Dripping with sweat, we whirled from corner to corner, like movie detectives clearing the room, finding still more drunken cockroaches to kill.

We killed all we could find, overturning the mattress and tearing apart the bedding, shaking out the nylon curtains, and sweeping under the bed to find the last stragglers. When we had finally killed them all, Ken fetched the broom and the dust-pan and began sweeping up the carcasses. Perhaps in fear that his new bride would promptly flee the country, or at least demand an air-conditioned hotel room now, he tried to laugh, determined to make the best of it. “Well,” he said, “it could be worse,” as the first dust-pan full of dead roaches thumped onto the bottom of the trash-can. “No,” I said, “It really couldn’t.”

Of course it could have. We had cool showers to take and clean towels and nothing more problematic in our lives than the difficulty of falling asleep afterwards. But we did need to speak with Older Sister Lan about the những con gián. Con gián? She was shocked. In her house? No. She kept a clean house. We persisted, gently reminding her that in a market economy, tenants were free to move elsewhere. Finally, she admitted that something had happened. Her sister-in-law was suffering an infestation of con gián, and had used insect bombs on all three floors. The hordes of poisoned cockroaches had fled the insecticide, crawling underneath the adjoining doorways into our house to die.

We did move soon after, when we realized that the endless hammering of rebar stakes in front of her houses resulted from her renting out that workspace to newly-formed construction companies. We fled to a charming French colonial house on Banana Street with air-conditioning and cable TV (and where we could hear the termites chewing the wood floors at night). But before we moved, Ken brought home a gift from the field. It was an old rice whiskey bottle that had been filled with rare jungle honey and sealed with plastic wrap. When I opened it, anticipating butter and honey on my baguette, I was greeted by a dead cockroach that had found its way into the bottle before it was plugged, and was now preserved, amber-like, in the neck of a bottle. I ate the honey.

I didn’t know any of this about your history! Aside, great writing!

LikeLike